The future of agriculture lies in India

In February, a small delegation from the Global Field movement visited the Andhra Pradesh Community Managed Natural Farming (APCNF) movement in the southwestern Indian state of the same name. This was Benny Haerlin’s third meeting with the farmers and their “special advisor”, as Vijai Kumar Thallam modestly calls himself, following a visit in 2017 and a presentation at the Foundation on Future Farming “The Color of Research” conference in 2024. Here is his travel report:

When Sowjanya Soujanaya goes to her ATM garden in Edulamaddali in the morning, she not only finds enough herbs, spices and tubers to cook a healthy lunch for her family of five, but also something she can sell at the market – ATM stands for “Any Time Money” and is a mixed cultivation of more than 20 different types of vegetables, berries, root crops and herbs on the 800 square meters in front of her house. The basic idea behind the cultivation plan is that something can be harvested and sold here 365 days a year.

She doesn’t need any pesticides or subsidized fertilizers, “it’s all natural!” laughs Sowjanya and you immediately understand how the young woman in the colourful sari has managed to get 2,300 followers on her YouTube channel #Dsthoughts: Life can be so simple, despite all the adversity and dangers. The keys to success are a few clear rules when using diversity, constant experimentation and accurate documentation of the results.

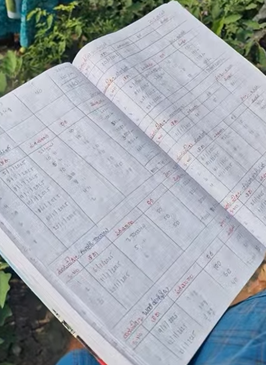

The model farmer, who has already trained several neighbors, meticulously records everything that happens in the ATM Garden in a thick book: Sowing, mulching, transplanting, pests, beneficial insects, preparations applied and, of course, the harvest, its weight, quality and the proceeds she has achieved. She sends important data by cell phone to the head office in Guntur, the headquarters and data center of the APCNF movement.

A third planting season

Last September, the surrounding fields were flooded for weeks. Sowjanya shows us pictures on her cell phone of her husband standing waist-deep in water in the rice field in front of their house. But then, they would not have thought it possible themselves, the rice rose again and, unlike the neighbor’s, still produced an acceptable harvest. She has written “Climate resilience” on the poster made of wrapping paper that the neighbor is now holding up, while Sowjanya talks about how, thanks to natural farming, the root balls have a wider and deeper base and soil fertility has already been significantly increased in the first year thanks to PMDS.

PMDS stands for Pre Monsoon Dry Sowing: Long before the rainy season in June, a mixture of 32 different seeds is planted in the bone-dry soil, which is exposed to the merciless sun in neighboring fields, naked, hard and dusty. They germinate even without rain because they have previously been carefully coated in several layers with a mixture of manure and nutrient preparations, water, clay dust and ash. This pelleting makes it possible for “the desert to turn green” as early as April. This creates a third season between the two traditional planting seasons (Kharif in summer and Rabi in winter).

The PMDS mixture

Maize, millet, mustard, castor, yellow lentils, green lentils, red lentils, coriander, chili, hemp, pillipesara, sunflower, tomato, bhendi, eggplant, amaranth, red sorrel, runner beans, methi, spinach, marigold, mustard, black lentil, cowpea, bajra, ragi, sesame, horse grass, sorghum, field beans, yarrow, sesbania

The plant mixture in the fields “harvests” the missing water from the dew in the morning and water vapor in the air; the larger the biomass, the more effective. And the more porous and rooted the soil is, even in deeper layers, the more moisture it stores in its interstices. They are created by the diversity of roots and their microorganisms and are maintained over the years by minimal soil cultivation.

This organic loosening, the opposite of the usual soil compaction, improves the water balance and revitalizes the soil by creating ideal living conditions for the soil microbiome. It is one of the central principles of the Natural Farming program, which has developed extremely dynamically over the past 10 years.

Feeding and nurturing the microbiome

At first glance, natural farming differs from chemical farming (which no one in India calls “conventional farming”) not only in its diverse mixed cultivation, but also in the use of a range of biostimulants, especiallyJeevarutham, a recipe made from fermented cow urine and manure, cane sugar, legume flour, water and fertile soil. This does not serve to supply the plants with nutrients, but promotes germination on the one hand and the development of a diverse microbiome of bacteria and fungi on the other, with the help of which the plants obtain the necessary micronutrients from the soil.

The basic idea behind this is that plants put around 40 percent of the sugar production from their photosynthesis into the above-ground biomass and 30 percent into the roots. They use the remaining 30 percent to feed fungi and microorganisms in the soil, which return the favor with other nutrients.

Firstly, the right mix and sequence of plants with their specific composition of roots, foliage and exudates, secondly, the maximization of the biomass produced and metabolized and thirdly, the development of a stable, diverse microbiome, according to the natural farming theory, are sufficient, at least under the subtropical cultivation conditions there, to provide and mobilize all the nutrients required by the crops grown. Even the biostimulants are largely dispensable in the long term once the right, locally adapted microbiome has been established and stabilized.

“There is no need for a gram of external nutrients, whether synthetic or organic” is the radical thesis that over a million farmers in Andhra Pradesh are now successfully working to prove. In combination with the plant residues remaining in and on the soil, according to another theory, it does not take the proverbial centuries to build up and restore fertile topsoil. A few years are sufficient for regeneration if sufficient biomass with the right consistency and biological dynamics is continuously incorporated into the soil. The right diversity of plants and microorganisms is also crucial here.

The nine principles of natural farming

1. the soil must be covered with crops 365 days a year (principle of living roots)

2. large variety of crops, 15-20 species, including trees

3. Keep soil covered with plant residues whenever no living plants are growing on it

4. Minimal disturbance of the soil – minimum tillage

5. Use farmers’ own seeds. Give preference to indigenous seeds

6. Integrate animals into agriculture

7. Use biostimulants as catalysts to activate soil biology

8. Plant protection through better agricultural practices and botanical pesticides

9. No synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides and weed killers

Farmer’s innovation: the driving force

The representatives of the APCNF attach great importance to the fact that all these agricultural paradigm shifts are based on traditional and indigenous knowledge of the region, but in their current form are modern, science-based cutting-edge technology inspired by a number of leading soil microbiologists, most of whom conduct research in the USA and Australia. These new technologies are put into practice and further developed from practical experience primarily by farmer scientists on the ground.

Through observation and experimentation, careful documentation, exchange and repetition at different locations, they develop new models for the various crops and cultivation systems. This involves new combinations and, as a rule, even more diversity in the fields, the integration of palm, cocoa and fruit trees; but also the use of drones to apply biostimulants to rice fields, new pumping and irrigation systems or quality determination by measuring the sugar dissolved in the plants. Once fully developed, they are then disseminated quickly and on a massive scale as an “A-class model”. In the case of Pre Monsoon Dry Sowing, after the first 11 pilot fields in 2018, the number of participating farms increased from 21,000 in 2019 to 863,000 in 2023, and the area from 15,000 to 385,000 hectares.

Since 2023, RySS has been offering a four-year Bachelor’s degree program for women farmers through the Indo-German Global Academy for Agroecology Research and Learning (IGGAARL) with a loan from the Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau, KfW, in which 500 students are trained primarily by 180 farmer mentors. 75 percent of their studies take place in their own fields, supported by online mentoring. The final project is also their own field and a presentation about it to their neighbors.

The guru and the bureaucrat

It all started with a guru and a bureaucrat. The guru, Subhash Palekar, had developed a farming system from studying traditional agricultural practices in India, which he called “Zero Budget Natural Farming” because it guarantees farmers a secure income without external costs. Indebtedness at usurious interest rates for the purchase of chemicals and seeds is a hostage to rural development throughout India. It bleeds more than half of the country’s 120 million farming households dry and is the cause of thousands of farmer suicides every year as they lose their land to loan sharks.

Palekar initially preached his new methods of dealing with Mother Earth with spiritual urgency and great charisma at gatherings of thousands of farmers lasting several days. But after such awakening experiences, he left the newly won disciples to their fate and moved on.

Vijay Kumar Thallam had just retired as a civil servant ten years ago. Since the 1980s, he had played an important role in supporting village women’s self-help groups, first in Andhra Pradesh and then with the central government in Delhi. Palekar’s cultivation concept convinced him. However, he felt that there was room for development in building dynamic structures to spread it. Together with a few like-minded people, he founded the non-profit company RySS, Rythu Sadhikara Samstha, which roughly translates as Farmer Empowerment Organization.

Kumar welcomes us to the RySS headquarters in an unadorned exposed concrete building on the dusty outskirts of Guntur, one of the administrative centers of the state where the “green revolution” began in India in the 1960s with high-yielding varieties, massive irrigation and increasing amounts of artificial fertilizers and pesticides. Now, he hopes, a new, truly green agricultural revolution could start here.

From soil and village structures

Independent of state institutions, albeit with massive financial and organizational support from the state of Andhra Pradesh, whose successive governments have been committed to switching to APCNF for ten years, RySS has been systematically establishing and expanding the new cultivation methods since 2016 with an increasingly sophisticated education and development system that is tailored entirely to smallholder farmers and relies on their own powers of persuasion and innovation. “The art of upscaling,” says Kumar, “lies in the right mix of clear and simple rules and enough leeway for the strength, pride and inventiveness of each individual, of trust and control, solidarity and science.”

The fact that the APCNF movement has covered over a million farms in ten years is the result of meticulous planning and the gradual establishment of self-sustaining and innovative structures. In the often encrusted hierarchies of Indian society and state bureaucracy, this is not a matter of course.

Individual farmers are not only trained in the application of agricultural methods, but also in their communication. “Champions” show how it works in their fields, document exactly what was done and what was avoided and what is harvested, what adversities occur and what measures and preparations are used to overcome them and how effectively. “We don’t want to convert individual farmers, but entire villages, starting with the small farmers and the poorest of the poor, who have no land at all,” he explains his strategy. “Everything has to pay off from the outset so that it convinces people who have no reserves.”

The majority of those involved in APCNF cultivate one to two acres, 4000 to 8000 square meters. 10 acres, a good 4 hectares, is already a sizeable farm and 50 acres already make a large farmer out of its owner, who already pays a whole team of seasonal workers a meagre daily wage of around 200 rupees, just over 2 euros. The average size of all farms in India has fallen from two to one hectare since the 1970s.

Smallholder ecology – It’s the economy, stupid!

Precise recipes and cultivation plans, exact cost, harvest and yield figures and comparisons between neighboring natural farming and chemical farming fields are displayed on large banners directly on site, including the failures that are also documented for natural farming.

The arguments put forward by APCNF are compelling: hardly worse, often better harvests, but in any case a significantly higher profitability for the farmers, who do not have to buy expensive inputs and always harvest a variety of additional vegetables, herbs, nuts, oilseeds and pulses in addition to their main crop. The women farmers in particular see the greatest advantage in the improved health for the whole family through good, varied nutrition and the avoidance of pesticides. In addition, there is the consistent improvement in soil productivity through additional harvests and greater resistance to heat, drought, floods and heavy weather such as the regular tropical cyclones that hit Andhra Pardesh from its 1000-kilometer coastline. Added to this is the economic revival of the village through local sources of income such as the production of various preparations and the first forms of cooperative marketing of surpluses that do not serve the subsistence of the community.

Don’t leave the economy to the men

The strong backbone of the movement are the local women’s self-help groups, which play a key role in the economic transformation as savings associations, lenders and guarantors. This is because APCNF does not rely on any state agricultural subsidies, such as those that flow massively into cheap mineral fertilizers in India. The local self-help group finances the independent purchase of the cow that is indispensable for the preparations, the necessary basic equipment or the first lease for women farmers who are setting up their own business. Punctual repayment is a matter of honor, as is solidarity-based support in many life situations in the patriarchal village society.

Not only since Angela Merkel presented him with the prestigious Gulbekian Prize for Humanity in 2024 has Kumar been convinced that APCNF is the right solution for sustainable, climate-adapted and resilient agriculture, poverty reduction and healthy nutrition far beyond Andhra Pradesh.

More than just an ingenious cultivation method

At the end of the year, he was finally able to convince the Indian central government to test and propagate the model in other states of the country. His radical questioning of all their chemistry-based paradigms is still anathema to the grandees of the agricultural universities. Despite all the international scientific confirmation that the method has now received, the ageing elite of chemical agriculture still regard it at best as a care measure for the poor. Yet, in addition to the direct benefits for small farmers, it can make an invaluable contribution to solving the major challenges: climate protection and adaptation, soil conservation and water management, avoiding poisoning and over-fertilization, improving health, food quality and micronutrient supply and, last but not least, a rural economy oriented towards the common good that could put a stop to rural exodus. The belief in the many and the power of diversity is far more than just a farming method.

Global Fields in schools: New educational initiative?

Following the visit of the Global Field delegation and the exchange on natural farming, global agriculture and education, the APCNF movement is now pushing ahead with the establishment of several world fields. These are to be set up at schools on the one hand and planted by experienced “farmer scientists” on the other. The exciting thing about natural farming Global Field: it will be about a livelihood Global Field. How much arable land does an Indian family need to eat healthily and generate the necessary income? How much arable land does a person need in natural farming to eat healthily and sustainably? We will soon be experimenting with these questions.