Cashew tree, Anacardium occidenta

Area globally: 6.1 million hectares

Area on the Global Field: 7.3 m² (0.4%), replacement crops on the Global Field

Region of origin: Northeast Brazil

Main cultivation areas: West Africa, India, Vietnam, Brazil

Uses / main benefits: Snacks, in sweet and savory dishes, oil

It looks inconspicuous, but is full of surprises: The cashew is not just a snack, but also an economic factor, sustainer of livelihoods and a source of innovation all at once. A closer look reveals a story of toxic shells, tropical apples – and an attempt to bring fairness and sustainability to a global supply chain.

The tree with two faces

The cashew tree is a robust, evergreen tropical tree that can grow up to twelve meters high. It belongs to the botanical family Anacardiaceae, a large family of tropical and subtropical trees and shrubs. There are also many different cashew trees that grow between 80 centimetres and 40 meters high. The common cashew tree, which is cultivated in agriculture, grows between 10 and 12 meters high. The cashew tree likes very sunny, dry and sandy soils. It is very sensitive to cold and cannot tolerate frost. The first flowers only form between the third and fifth year and nuts can be harvested from around the eighth year.

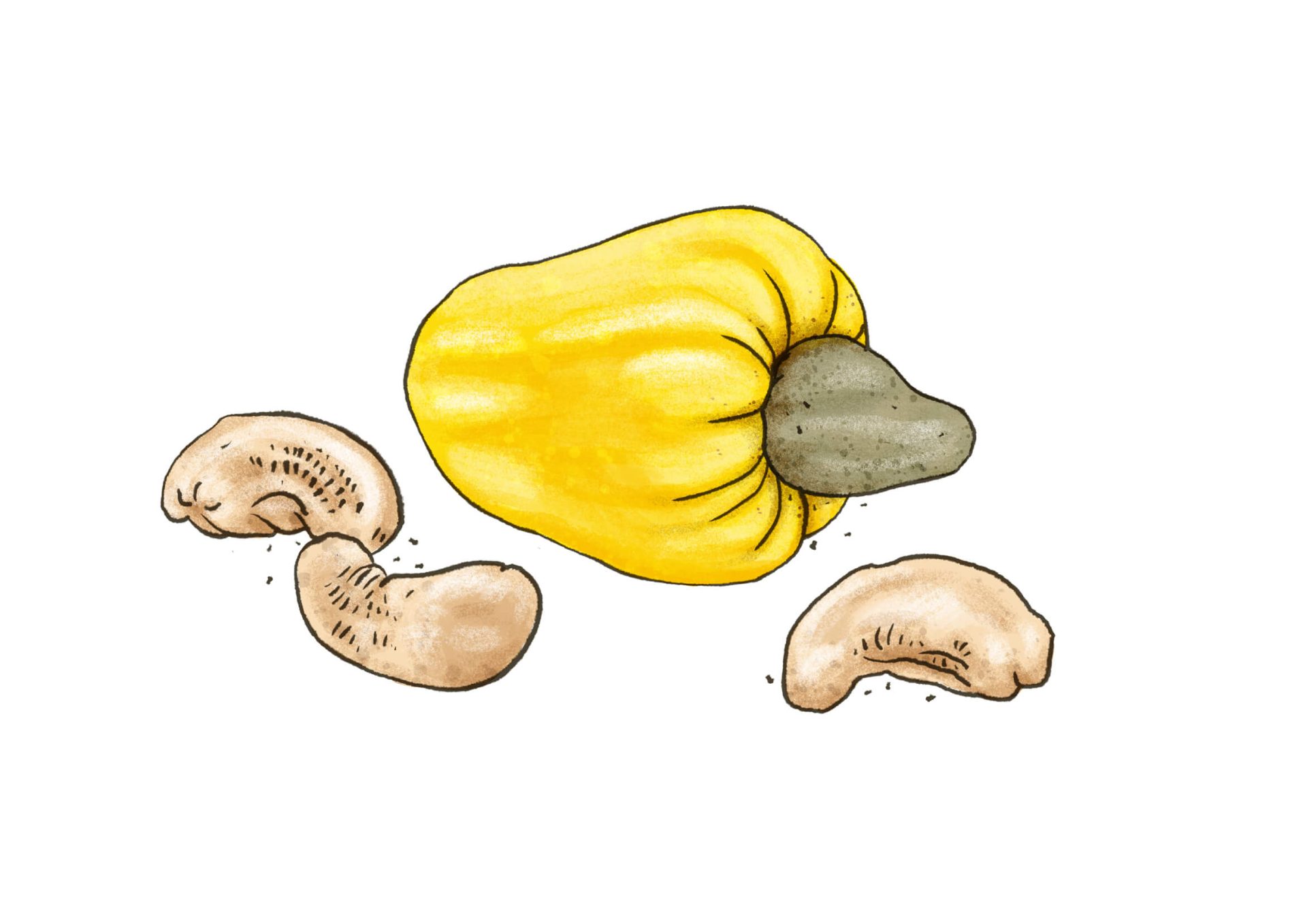

The unusual fruit formation of the tree is striking: the actual nut hangs at the end of a fleshy, bright yellowish red fruit stalk – the so-called cashew apple – enclosed in a hard, double-layered shell. While the cashew apple is eaten fresh in the countries where it is grown or processed into juice and spirits, outside the countries where it is grown, the nut is almost the only thing that is known. However, they have to be peeled and de-oiled at great expense, as their shells contain a skin-irritating oil – similar to the toxin of the related poison ivy plants.

The elephant spreads the cashew

The cashew tree has its origins in Brazil. Portuguese conquerors first brought it to Mozambique and India in the 16th century. It was originally cultivated as a coastal protection to prevent erosion. The cashew apples were a tasty treat for the elephants in these countries. They ate the fruit with the nuts on the coast and then moved across the country. As the nuts were too hard for them to digest, they excreted them whole and thus spread cashew trees throughout the countries. So we can thank our big, grey friends that the cashew nut is so well known today.

Cashew plantations were established in the 19th century and cultivation spread to other countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Today, the center of global cashew production is in West Africa – countries such as the Ivory Coast, Nigeria and Ghana are among the most important producers. India and Vietnam are also important cultivation areas and dominate industrial processing. This is because the cashew nuts grown in Africa, especially by smallholder farmers, are mostly exported to Asia for further processing – a fact that has led to debates about value chains and fair pay.

Not only the seeds taste good

Cashews are not only delicious, but also nutritionally valuable. They contain high-quality vegetable fats, plenty of protein and a considerable amount of minerals such as magnesium, iron, copper and zinc. They are therefore popular with people who follow a balanced or plant-based diet. In the kitchen, they are real all-rounders: whether on their own as a snack, as a vegan alternative to cheese and cream or as an ingredient in sweet and savory dishes. Around 60 percent of cashews are eaten as a snack, while the rest are used in sweet and savory dishes.

However, not only the kernels can be used, but also the cashew apple and the nutshells. The nutshells are rich in tannins, which are extracted and used to tan leather. The cashew apple is a prized food in Brazil and other growing countries – often enjoyed freshly squeezed as a juice rich in vitamin C or processed into jam. But cashew wine is also produced: a light yellow alcoholic drink with 6 to 12 percent alcohol.

Dangerous work for low wages

Processing the cashew nut is a complex process. The shell contains a corrosive oil that can irritate the skin and respiratory tract, which is why it must be removed before consumption. In many countries, shelling and roasting is done by hand, often under precarious conditions. Many workers, especially women, are exposed to unprotected health risks. Cashew production is also economically unstable: smallholder farmers are heavily dependent on international market prices, which can fluctuate. In addition, the growth of the trees and the harvest are very dependent on the weather, which means that producers are exposed to annual variations. The harvested nuts must meet high quality standards in order to be competitive on the international market. In addition, cultivation in monocultures promotes soil fatigue, reduces biodiversity and makes the trees more susceptible to disease.

New paths for the cashew

Awareness of fairer and more environmentally friendly production methods is growing in many growing regions. Projects in West Africa focus on local processing, fair wages and training in agroecological methods. Certifications such as Fairtrade or organic help to create better working conditions while maintaining ecological standards.

Exciting innovations are also emerging in Brazil, the home of the cashew tree: The start-up ‘Cajú Love’, for example, uses the previously largely unused cashew apples – the fleshy fruit stalks on which the familiar nuts grow – to produce a plant-based meat alternative. So far, only a fraction of the so-called ‘cashew apple’ in Brazilian plantations is normally processed – the majority rots unused on the plantations. Founders Alana Lima and Felipe Barreneche discovered the potential of the fibrous, sweet and sour fruit and used it to develop a vegan product that tastes like chicken, pork or tuna. According to the company, over 105,000 cashew apples have already been used since it was founded in 2021 – an initiative that not only reduces food waste, but also creates new sources of income for local farmers.

These developments demonstrate that the cashew has far more to offer than just its nut. From sustainable cultivation and fair value chains to innovative products made from previously neglected parts of the plant – the potential of this crop is far from being exhausted.

Sources

Oliveira et al (2019): Cashew nut and cashew apple: a scientific and technological monitoring worldwide review. Link.

FAO (2001): Small-scale cashew nut processing. Link.

Proplanta: The cashew apple – untapped potential. Link.

BUND: The arduous journey of cashew nuts. Link.